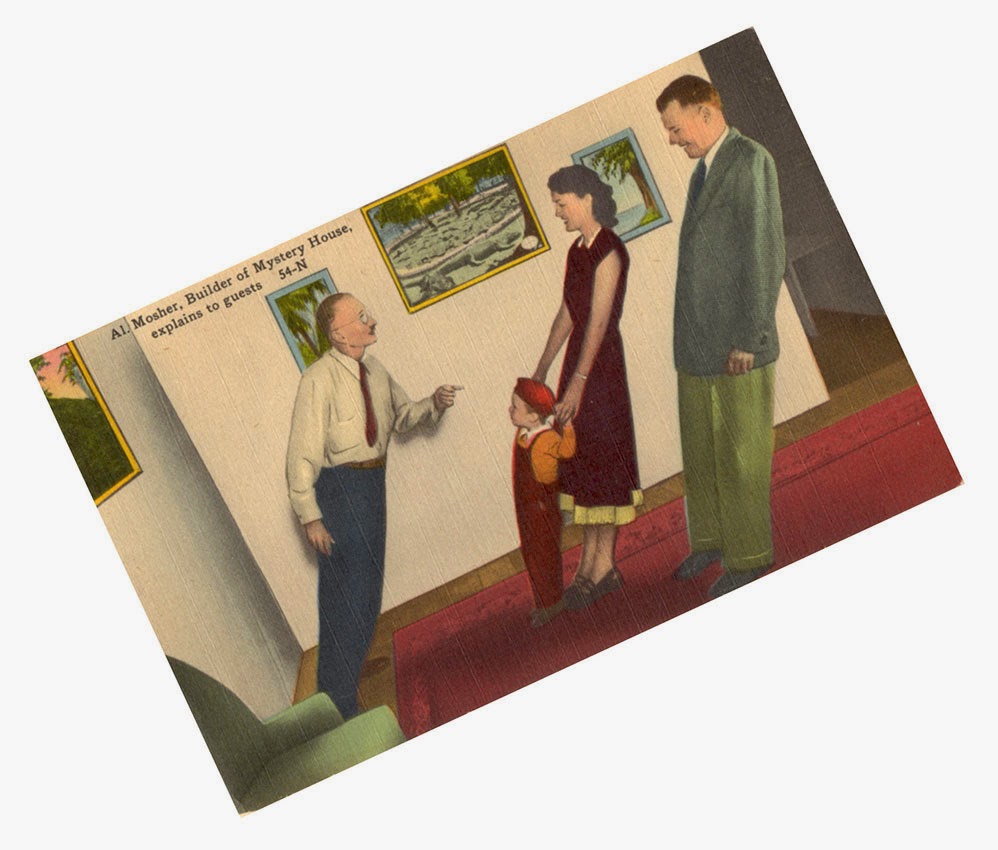

Eye-witnesses report that it wasn’t unknown for visitors to this unusual Florida attraction to be overcome with disequilibrium-induced nausea and exit the house vomiting copiously, although this wasn’t mentioned in the publicity. As it says on the reverse – cross the Bridge of Lions, just opposite the St. Augustine Alligator Farm on Route A1A – and you’re there. It takes a leap of the imagination to come up with an idea like this and a justly proud Al has the air of a born teacher as he explains his creation to Mr and Mrs Average and Junior. There should be one of these in every town if only for the pleasure of submitting a Planning Application and hearing what Building Regs. have to say about it. With Mr Pickles still in charge of national planning policy and prioritising economic potential, there really should be no obstacles.

Tuesday, 16 December 2014

Thursday, 11 December 2014

Aerial Visions – the Flight of the Mind

There’s a lot of speculation on the influence of photography from an elevated viewpoint on the way we model the world in our imagination. The proposition is that before the development of the skyscraper and powered flight it was very difficult to conceive of how the world would appear from above and that artists exploited this shift in viewpoint into new and dynamic forms. Tall structures, often in the form of fortifications or bell towers certainly existed in the past but artists made little of the opportunities they offered for taking a radically fresh viewpoint on familiar things. Kirk Varnedoe wrote in A Fine Disregard, 1990, about the fundamental shift in viewpoint in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that inspired artists and photographers from Degas and Caillebotte to Malevich and Rodchenko to reimagine conventional pictorial space and explore a new vocabulary of form. The subtitle, Flight of the Mind was his phrase to describe what happened when Rodchenko’s photographs “broke the axis of relation between the horizon and the ground”.

I suspect I’m far from alone in deriving great pleasure from examining the world below from a position of great height. It’s not the distant horizon that commands my attention but what is more or less directly below my feet. When elevation supplies a panoramic view it’s always interesting but the spatial recession of patchwork fields, human settlements, rivers, hills and valleys, whether pictorially harmonious and uplifting or darkly sinister and unsettling, is a familiar sensation. The natural topography of the planet delivers an abundance of vantage points which it could be argued we are evolutionally programmed to note for their values as defensive or offensive positions. What is least familiar to us is the space we inhabit as seen from directly above our heads – when what we normally see only in elevation is suddenly visible in plan. New and unanticipated formal relationships are revealed in which abstract qualities predominate. Physical elevation offers the reverse of the vision of the infinite and sublime that a painted ceiling by an artist like Tiepolo is intended to evoke. Instead of looking upwards and sensing our insignificance, we look downwards and indulge the fantasy of possessing mastery over our personal Lilliputian kingdom below.

These photos of Turin were taken from the observation deck of the Mole Antonelliana, an odd and over-ambitious building, planned as a Synagogue on an epic scale, that had to be rescued and repurposed when the money ran out and construction was abandoned. In form it’s a bizarre vertical stack with a pagoda-like pinnacle on top of a double-height temple on top of a duomo on top of a gallery on top of another classical temple. After 15 years of painfully slow construction the city authorities took over the completion of the building, finally achieved in 1889, and it’s currently put to use as a National Museum of Cinema. A glass-walled elevator transports the public in a vertiginous parody of the Ascension through the dead centre of the duomo and onwards to the deck above. These photographs are a record of what became visible when the city of Turin was rotated through ninety degrees.

Labels:

aerial views,

Italy,

photography,

torino,

turin

Friday, 5 December 2014

Postcard of the Day No. 70 – When Two Heads Collide

Even I hesitated for a moment before spending the princely sum of 10p on this postcard. Despite being good value for money, I sensed that this was an image that once seen could never be erased. Some staggeringly wretched postcards have turned up in a lifetime of collecting but in terms of content, conception and sentiment, this is desperately close to an all time low. A grim fascination compelled me to buy it – I tried to convince myself that it was a satire on the manners of the time but my heart wasn’t really in it – it must be taken as it is.

Even her hat is wrong – distorting the shape of her head and adding prominence to her pointy chin. But far worse are the frozen parted lips and exposed vampire-like top set of dentures. Together with the eyes, that subtly aim in two directions, they don’t suggest an imminent surrender to erotic passion. If anything our Adonis is even more disturbing – his neck has been removed and his eyes appear to be watching the clock. His lips are pressed ineffectually against his beloved’s chin as he wonders just how long this torment will last. It’s an enactment of osculatory hydraulics from which the warm glow of Romance is excluded. No soft-focus lens to seduce the eye – the full horror is revealed in the harshest of light.

An Edwardian suitor could choose from thousands of cards of courting couples – this would have to be the last one in the shop to be selected to guide Cupid’s arrow in the direction of the object of his affections. Sending such postcards was a way of communicating amorous intent in an age when the prevailing code of conduct made it almost impossible to express in any other way. There’s a reproachful tone in the message at the top – a suggestion that the recipient may have been bestowing favours outside the relationship. Leading us even further into dark waters is the space in which the sender can nominate a location for this dishonourable behaviour. It may be much safer to send something like the example below. Birthday greetings expressed in verse (complete with misprint), a gift of flowers, curtains parted in promise, an upturned moustache, a roguish eye and an air of consummate self-satisfaction.

Wednesday, 3 December 2014

Chevrolet 1957 – sweet, smooth and sassy

1957 was a big year for Chevrolet. As America prospered, motor styling became increasingly rapturous – a ballistic missile/jukebox aesthetic was evolving fast and would soon achieve its apotheosis. The ’57 Chevy is still one of the most highly regarded classic cars and the most cherished model is the Bel Air (below). Massive advertising campaigns were essential to drive demand for the annual face-lifts and Chevrolet business was handled by the Detroit based agency, Campbell-Ewald. In general I feel no great affection for motor cars but the feverish insanity of 1950’s Detroit overcomes my resistance. I’m old enough to recall what boring things English cars were in this period – styled like Victorian sideboards and marketed by association with upper-class snobbery – shown against an endless backdrop of fox-hunting, stately homes, golf courses, debutantes’ balls, Dickensian coaching inns and cocktail parties with uniformed flunkeys in attendance.

The Campbell-Ewald approach is much more to my liking – a cheerfully assertive message that you’ll miss out on something wonderful, exciting and life-enhancing if you don’t trade up to the very latest model with the unspoken message that nothing spells failure more clearly than being seen in last year’s model. Illustrators still got more work than photographers and dramatically exaggerated the dimensions and detailing on the vehicles into ecstatic visions designed to leap off the page and arouse the motorist’s deepest desires for status, speed and comfort. The advertising tag-line of the year was the alliterative “sweet, smooth and sassy” – sweet to taste, smooth to the touch plus a gentle nudge towards the erogenous zones. How else to describe the Triple-Turbine Turboglide? A second tag-line from 1957 was “velvet smooth and full of spunk” leaving even less to the imagination. I shudder to think what a British audience would have made of language like this. This selection features the work of the following illustrators, Alex Ross(2), Stan Galli, Bruce Bomberger(2), David Lindsay, Charles Allen and Paul Nonnast.

Labels:

advertising,

americana,

cars,

chevrolet,

detroit

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)