Classic Guinness advertising took divergent paths. In one direction were the boldly drawn John Gilroy menagerie compositions and feats of prodigious strength with brief snappy slogans. In another was a long series of pretentious, whimsical, text heavy magazine adverts in which the over-educated copywriters at S H Benson indulged their fondness for elaborate demonstrations of literary expertise and witty wordplay. Placing the adverts in such publications as Illustrated London News, The Tatler and Country Life represented a conscious effort to reach a more affluent and socially superior consumer. The hallucinatory fantasies of Lewis Carroll were extensively parodied in sometimes interminable verses, deep in which the merits of a glass of Guinness were archly commended. The saving grace was in the accompanying illustrations, especially those of the under-rated Anthony Groves-Raines who possessed a genuine flair for elegantly deadpan rendition of fantastical subject matter. Groves-Raines had a long association with Guinness and was a regular contributor to the series of illustrated brochures that Guinness dispatched to the nation’s doctors every Christmas. One of these, (My Goodness! My Gilbert and Sullivan) was posted on this blog in 2010. Brian Sibley in The Book of Guinness Advertising (1985 and still the definitive book) has chapter and verse on this topic on page 73, (Guinness in Wonderland).

Saturday, 30 January 2016

Tuesday, 19 January 2016

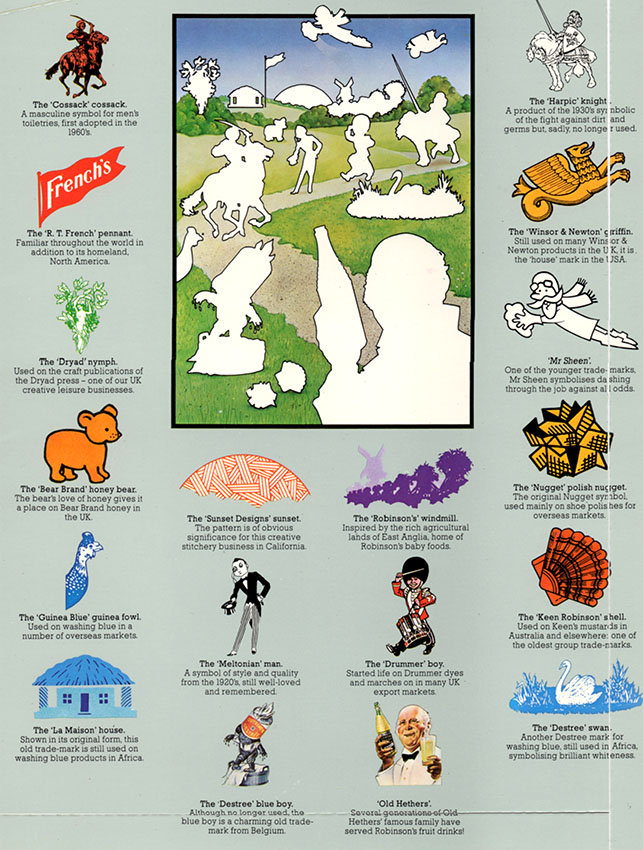

Wandering Brands

Reckitt and Colman was able to assemble this disparate collection of brand characters to grace the covers of its Annual Report in the 1980s. Many of these mascots, so artfully combined, have wandered off in all directions while the parent company merged with a Dutch business becoming Reckitt Benckiser in 1999. Since then the name has been abbreviated to the not very inspirational RB. While Harpic, Dettol, Brasso and French’s Mustard remain part of RB, others have moved on to new ownership (listed below) and a few (Robin Starch, Wren’s Shoe Polish, Drummer Dyes, Bluebell Polish) seem to have vanished leaving very little trace. Even where the products survive many brand characters have been retired and although some are no great loss, the world seems a poorer place without the jaunty monocled Meltonian Man bringing the sparkle of the Drones’ Club to an otherwise unexciting range of shoe care products.

Colman’s Mustard – now Unilever

Robinson’s Drinks – now Britvic

Reeves – ColArt (majority owned by Linden Group, Sweden)

Winsor & Newton - ColArt (majority owned by Linden Group, Sweden)

Cherry Blossom – Granger’s

Propert’s – Kiwi (S C Johnson, formerly Johnson Wax)

Meltonian - Kiwi (S C Johnson, formerly Johnson Wax)

Saturday, 9 January 2016

Car Plants

This is from the pages of Fortune magazine dated April 1944, two months before the Normandy Landings. A brace of shirt-sleeved execs, draft-exempt, kneel on the grass planting the seeds of the post-war rebirth of the auto industry. A hefty block of text explains what’s going on. In the flowery prose favoured by Ivy League-educated copywriters too old to be sent to war, we’re informed that this is the Victory Garden in which a new generation of cars is incubating. The technical advances of a war economy will lead to an innovatory paradise in peacetime. It’s a very odd way to illustrate a concept that most would think so slight as to be not worth the bother. Fortune was full of ads like this where the reader can be forgiven for concluding the entire exercise is otiose. My suspicion is that the advertising sales team at Fortune were adept at out-thinking the masters of persuasion and all too easily induced businesses to take out full page ads they had no real need for resulting in page after page of almost content-free advertising. The killer line was “Tell the readers what you’re contributing to the war effort because all your competitors are.”

The illustration is the work of Slayton Underhill (1913-2002) - a name that sounds more like a Wall Street brokerage or a Purveyor of Fine Tobacco. Underhill was one of many mid-century illustrators who toiled away in the industry without reaching the top flight of illustrators that commanded the highest fees. Underhill’s fame rested on his ability to create a paint finish utterly depersonalised and anonymous, scrupulously eliminating all evidence of material handling. This early example shows a certain technical bravura that the mature Underhill would never have allowed. The companion piece from Underhill was painted for Metropolitan Life Insurance. It’s a limp image of listless horticulture – a middle-aged widow sorrowfully reflects on the financial irresponsibility of her late husband in failing to provide the security of a Metropolitan policy. She is presented to us as a fallen woman, raising the fear she may be forced into prostitution to survive – an unthinkable fate for a decorous, unassuming flower of American womanhood. We will feature more of Slayton Underhill at a future date – be assured, it’s not all as dull as it appears here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)