Victorian printing technology steadily advanced through the 19th. century towards the ultimate goal of mass production of photographic imagery. Along the way the process of printing from engraved imagery on steel plates was constantly refined and improved. Engraving specialists were kept busy by the demands of mass circulation magazines (The Graphic, Illustrated London News, The Sketch, Punch) for new material to entertain the readers. Pictorial representations of current events, portraits of the great and the good, celebrity portraits and cartoons were especially in demand. Another army of engravers were preparing print versions of critically approved paintings as shown in Royal Academy exhibitions to enable the rising middle classes to display their taste for the visual arts on the walls of their own homes. Even more were engaged on topographical subjects - scarcely a manor house, ruined abbey or castle, riverbank, forest, lake, moorland or mountain went unrecorded. There was an affordable prospect for every affluent customer. The finest of these practitioners achieved spectacular effects in terms of describing detail and creating subtle and dramatic tonal effects through the precision of their mark making. Reproducing engineering drawings was a highly specialist skill requiring perfect clarity of visual description - this is a section of examples taken from the plates of various encyclopaedias. They offer impressively analytical images of new applications of steam power and increasingly complex machine technology. Starting with the printing industry, the application of steam in shipping and railways, the selection is completed with a variety of mechanical wood saws. Admire the delicate subtleties of tone, the impersonal drawing and the complete absence of visual rhetoric.

Tuesday, 27 July 2021

Friday, 9 July 2021

John Hassall - Poster King

John Hassall is having a moment. There’s a comprehensive exhibition of his work at the Heath Robinson Museum in Pinner (ending on August 29) accompanied by a new book, The Life and Art of the Poster King by Lucinda Gosling (Unicorn, 2021). This recognition is long overdue - there has been a persistent reluctance on the part of museums to exhibit the work of graphic artists whose output fell, for the most part into the category of what used to be called commercial art. The sense that the association of art and advertising is unworthy of close study never quite goes away, along with the gulf in status between Fine Art (engages the higher faculties) and Advertising Art (vaguely disreputable, appeals to the coarser instincts). Curiously as state patronage of the arts declines the art world has been forced into an ever closer funding relationship with the world of business and finance whose tolerance for sponsoring work that questions their activities often wears thin resulting in hidden pressures to focus on work that more closely aligns with corporate interests. In this context the straightforwardly transactional nature of the work of artists like Hassall can seem less compromised.

The book is superb - the author has unearthed some rarely seen items and chosen to display in depth rather than showcase prime (and often over-familiar) examples. The selection of thumbnail images is generous and judicious and gives a much better impression of the range of Hassall’s output than I’ve ever seen before. Two column text blocks and visual material are well balanced and make for clarity of design. Pictorial boards, illustrated endpapers and a stitched-in bookmark make an excellent package and the absence of a dust-wrapper is something to celebrate. Hassall’s productivity was a match for Tom Purvis and some of his drawing has the toughness and muscularity of that of Purvis.

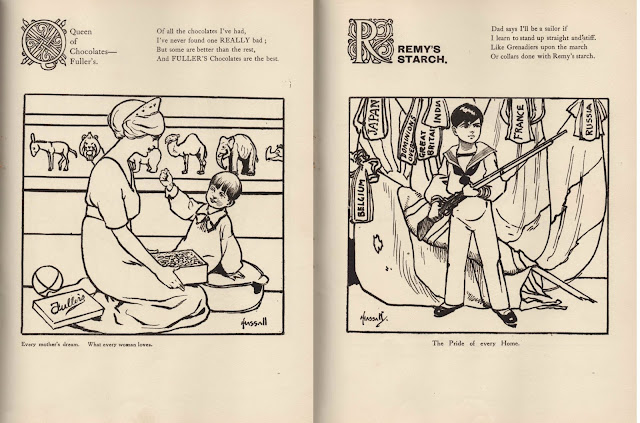

Hassall produced all the artwork for this colouring book for children in support of the Belgian Relief Fund in 1914. The Belgian nation has never been so popular with the British public as it was in the first year of the Great War. An intensive propaganda campaign in the popular press, demonising the German invaders for the ruthless cruelty inflicted on the civilian population created a great wave of public sympathy, of which this publication was one manifestation. It is striking to see the extent to which it combined philanthropy with commercial interests - every page had a business sponsor whose consumer products were publicised in Hassall’s drawings in the hope that their virtues would be embedded in young minds as their clumsy brushwork stuttered across the page. It was presented as an alphabetic sequence with accompanying versification. Allusions to military campaigns can be found but for the most part the patriotic note is one of restraint. Given the audience, images of children predominate and the war is very much off stage. None are especially memorable with the possible exception of the sturdy British youth who poses defiantly in his Pesco underwear with hairbrush at the ready, fully prepared to die for King and Country.