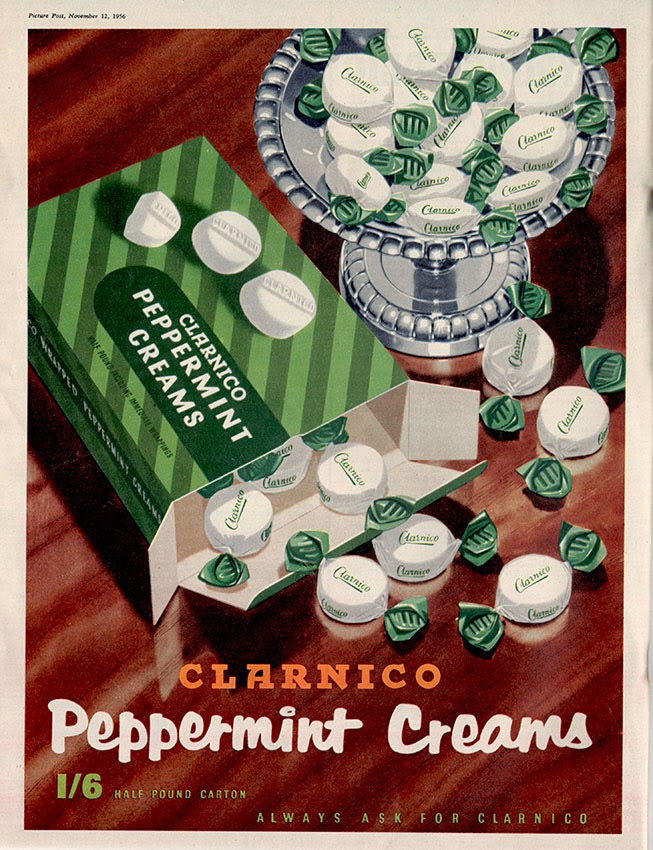

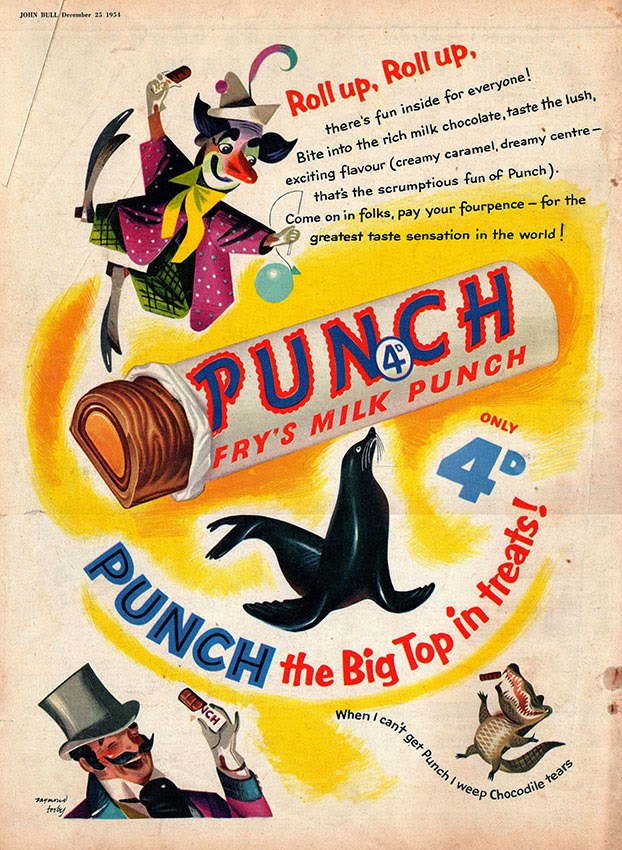

For a warm dose of comforting nostalgia there are few better triggers than childhood recollections of confectionery treats. Online protestations of undying affection for long forgotten sweets and chocolate are easily found. The attendant miseries and insecurities of childhood are erased by the power of pleasures recalled – unwrapping and consuming sugary, candied and chocolate-coated concoctions. For the immediate post-war generation these memories carry extra weight due to the imposition of sweet rationing which lasted until February 1953. The resulting expansion in demand is reflected in these full colour, full page magazine ads as manufacturers fought for market share in a new climate of plenty. An armada of temptation was mobilised to get Britain munching and chomping its way to the top of the international league tables of consumption. The dark clouds of rampant tooth decay and childhood obesity lay just over the horizon. A Conservative opposition fought, and almost won the 1950 general election on the issue of ending rationing while the Labour incumbents campaigned for indefinite retention. This began the process of stigmatising egalitarianism as a joyless and pointless aspiration, a denial of consumer choice and a symbol of the horrors of a planned economy, echoes of which persist to the present day. It was an early example of Labour politicians committing to unpopular policies – another tradition that survives.

Friday, 30 January 2015

Wednesday, 28 January 2015

Villaggio Leumann, Turin

Corso Francia is the principle westbound highway out of the city of Turin. It’s the main route from Piedmont to France and has been witness to many movements of troops of both nationalities in both directions as the two nations engaged in regular hostilities. The first settlement outside the city is the comune of Collegno and in 1875 Swiss textile manufacturer, Napoleone Leumann chose to relocate his business from Switzerland to Collegno for easier access to the Italian market for his products. Leumann was a paternalistic employer and took the opportunity to build housing and social facilities alongside his factories. Over the following three decades the site was developed to include housing for up to a thousand people, a church, public baths, a gym and a school. The designer was the engineer/architect Pietro Fenoglio who employed a sober, eclectic style very different from the flamboyant Liberty-styled house he designed for himself in Turin. (The Casa Fenoglio-Lafleur is about 5 miles to the east on the same road, Corso Francia.)

Fenoglio’s architectural contribution is difficult to quantify but the stylistic touches that pay homage to Leumann’s Swiss origins may well be his work. The pair of gatehouses are the most obvious examples with their hand carved wooden detailing and gingerbread air. Opposite the entrance is a modest timber-built rail/tramway station in a similar vernacular. The homes and factories are well proportioned and unassuming in style. The provision of gardens indicates the influence of British models designed to promote self-sufficiency and leisure time dedicated to labour and self-improvement. The textile business finally closed in 2007, after lingering on in a much reduced role since 1972 but the Villaggio Leumann has since been refurbished as a heritage site with some of the buildings converted into retail premises for the fashion industry. On a visit in October 2014 the housing stock seemed to be in very good order as were the retail units, but the major blocks, although recently repainted, still await a use. It was a Monday morning and there may well be busier times but there was very little sign of activity, economic or domestic. Other than the man who yelled from an upstairs window to tell me that photography was forbidden without a permit – an expression of resentment about being on public display.

Labels:

architecture,

fenoglio,

industrial architecture,

industry,

torino,

turin,

villaggio leumann

Tuesday, 13 January 2015

Marineland Oceanarium

Florida – Perpetual State of Wonders - Alligator Farms, Rattlesnake Ranches, Mystery Houses, Ringling Brothers Circus, the Green Benches, Fountain of Youth and the Singing Tower. Marineland opened in 1938 as the world’s first Oceanarium – a visitor attraction featuring sea dwelling mammals. Giant Turtles, Sharks, Whales and Porpoises drew in the tourists and the project borrowed a little literary respectability, having among its founders, Ilya Tolstoy (grandson of the great Leo and pioneer of underwater photography). Linen postcards offer the perfect medium for recording these sub-aquatic theatricals in which a changing cast of sea creatures swim around in the company of clumsy Marineland employees encased in diving suits constructed in an age of heavy engineering. I like these cards for their slow motion compositions and persistent air of absurdity – one or two of them could easily be taken for pieces of Performance Art. Follow this link to see what Florida offers today’s visitor – it’s an impressive range of implausible curiosities from which it’s difficult to select the most compelling but I wouldn’t want to miss the Atheist Monument, the Lowest State High Point in the US and the Garbage Truck Museum.

Labels:

americana,

florida,

linen postcards,

marineland,

postcards

Saturday, 3 January 2015

Dinner Hour Swindon

Not a bare head in sight as the artisans stream out of the railway works in Swindon, filing past the company-built housing (the Railway Village) after a busy morning building copper-capped steam locomotives for the Great Western Railway (GWR). Just a fraction of the 12,000 employees. They may have no NHS or JSA or Tax Credits or Sky Sports but at least they have a dinner hour – which is often more than today’s flexible and fragmented workforce can afford. The working day that was regulated by sirens and whistles is now more subtly regulated by zero hours contracts and ever expanding workloads coupled with the constant threat of unemployment – recent surveys (of doubtful provenance) on behalf of the food industry, show workers take an average of 29 to 33 minutes for lunch. Most depressing of all, one in seven employees hope to win favour with their managers by taking shorter breaks. Mass pilgrimages like this, to and from the workplace are part of labour history. Dispersal of workplaces diminishes opportunities for employees to organise and campaign for better pay and conditions. In the absence of collective action individual resentments accumulate and fester into a generalised reservoir of discontent from which the likes of UKIP draw their support.

At the age of 13 I once spent a Saturday afternoon on a tour of Swindon Works in the company of a like-minded group of train fanatics and social misfits whose ability to scrape through the Eleven Plus had been rewarded with a seven year sentence in the great Metroland Madrassa aka Watford Boys Grammar School. Our expedition leader was a gaunt and ascetic young man by the name of Rex who at 14 already resembled the Rural Dean and Antiquarian I fully expected him to become in adult life. It was a memorable experience – the last ever British-built main line steam locomotives were under construction on the factory floor. In one bay stood a completed example in all its resplendence, next to it was an almost complete example – in all about 12 locomotives presented a reductive display of disassembly, ending with a pair of sub-frames on which a number was chalked. The ethics of collecting numbers were called into question – could you really claim to have seen a locomotive when it was no more than a pair of metal castings resting on the floor?

Another assembly line was producing a batch of diesel-hydraulic locomotives – the first generation of diesel power, themselves doomed to a life of little more than a decade. Elsewhere steam locomotives of all vintages and size were undergoing repairs, surrounded by gleaming stacks of replacement parts, sets of newly turned and freshly painted driving wheels and trolley-loads of bearings, levers, rods, cranks and valves. Outside the works were the weathered and corroded remains of locomotives at the end of their working lives – in their dramatic decrepitude they were every bit as fascinating as the dazzling magnificence of the newly outshopped locomotives with their polished brass and sumptuous paintwork. The most exotic sight that day was an elderly narrow-gauge locomotive (No. 9 Prince of Wales) from the Vale of Rheidol railway that had travelled from Aberystwyth to Swindon on a flat-bed truck for repairs.

More than any of its competitors, the GWR worked hard to associate itself with the English landed gentry – the locomotives carried the names of Kings, Counties, Castles, Earls, Granges, Manors and Halls (some GWR directors were residents of homes that were honoured in this way), a constant reminder to travellers of the timeless hegemony of their superiors by birth. Although the green fields of Wessex were rudely bisected by Brunel as he pushed westwards, the knights and lords of the shires were handsomely compensated with easy access to the metropolis. Catch a cab at Paddington to a board meeting in the City, followed by a light slumber on the parliamentary benches. Lunch at a gentleman’s club might precede an adulterous assignation in Mayfair or Knightsbridge with the lubricious delights of an evening visit to a house of ill repute to look forward to.

In design terms the policy was to wrap advanced technology inside traditional forms – high-performance locomotives were styled to look like enormous pieces of mobile vintage furniture, composites of tallboys, sideboards and mantel pieces topped off with copper and brass trim and cast iron number plates, numerals burnished with gold leaf. Railway buildings took their features from the stables, workshops, lodges and estate buildings to be seen in the grounds of West Country stately homes. Architects borrowed freely from historical styles including Tudor, French Gothic and Georgian to build stations with an air of permanence as if the trains had been passing through for centuries rather than decades. Innovation and change made respectable by drawing attention away from its novelty and rooting it in the past. In the Victorian imagination, engineering excellence was just another manifestation of the eternally unrolling pageant of English pre-eminence.

Labels:

great western railway,

locomotives,

postcards,

railways,

swindon,

trains

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)