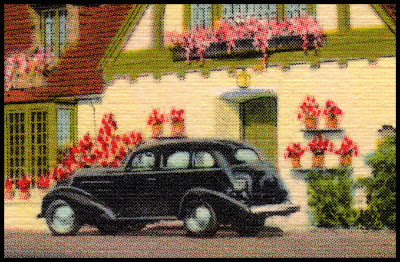

Post-war Britain was a curiously unsettled place as the fruits of victory rapidly turned sour. As the war battered economy struggled to rebuild, a sullen and increasingly discontented population was subjected to continual shortages of basic products. The age of deference and physical inhibition still prevailed and the stiffest of upper lips was required to endure the worst winter weather of the century. Nostalgia for the great days of naval dominance and imperial expansion was endlessly promoted, not least by advertisers whose imagination went no further than photographing a new car parked outside a half-timbered cottage accompanied by some deathless prose invoking the great traditions of British craftsmanship. Countless examples of this dismal level of invention can be found in the pages of contemporary magazines where the spirits of Shakespeare, Nelson or Dickens were held to be enough to inspire the consumer.

A visual image of a pastoral Britain, untouched by the ravages of warfare, industry or mineral extraction was cultivated in books for children and popular illustration. It was a land of peace and plenty where the social order went unchallenged and purposeful toil was the order of the day. After his years in the RAF studying aerial imagery, nobody was better prepared than Ronald Lampitt to bring this vision to life. All these examples of his magazine covers paint a picture of cosy reassurance designed to obliterate the unpleasant realities of post-war austerity. He had a sharp eye for vernacular detail and a perfect understanding of how distance could lend enchantment. The resulting images are a permanent delight for the wandering eye as we travel, with detachment, through the twists and turns of an idealised landscape entirely conceived for our entertainment.