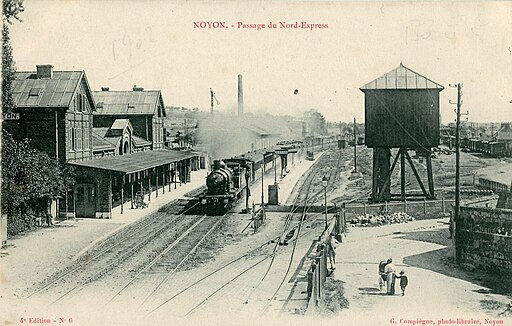

Writing in the New Yorker in 1948 (p 18, “Odette”, July 31st.) Vladimir Nabokov described the excitement of childhood train travel, looking back from his late-forties to his memories of the first decade of the 20th. century. The Nabokov family, in various permutations took the Nord Express from St. Petersburg (via Berlin, Köln and Paris) to Biarritz or the Côte d’Azur on at least five occasions between 1900 and 1914. A retinue of nurses, nannies and servants accompanied them and Nabokov recalled some of those journeys and the pleasures to be obtained by the simple act of looking through the window, in a New Yorker essay that was later revised to form Chapter 7 of his 1967 memoir, Speak, Memory (pages 104 to 108). These extracts give a flavour of his special talent for translating visual sensations into dazzling sequences of words.

The door of the compartment was open and I could see the corridor window, where the wire - six thin black wires - were doing their best to slant up, to ascend skywards, despite the lightning blows dealt them by one telegraph pole after another; but just as all six, in a triumphant swoop of pathetic elation, were about to reach the top of the window, a particularly vicious blow would bring them down, as low as they had ever been, and they would have to start all over again.

When, on such journeys as these, the train changed its pace to a dignified amble and all but grazed house fronts and shop signs, as we passed through some big German town, I used to feel a twofold excitement, which terminal stations could not provide. I saw a city, with its toylike trams, linden trees and brick walls, enter the compartment, hobnob with the mirrors, and fill to the brim the windows on the corridor side. This informal contact between train and city was one part of the thrill. The other was putting myself in the place of some passer-by who, I imagined, was moved as I would be moved myself to the long, romantic, auburn cars, with their intervestibular connecting curtains as black as bat wings and their metal lettering copper-bright in the low sun, unhurriedly negotiate an iron bridge across an everyday thoroughfare and then turn, with all windows suddenly ablaze, around a last block of houses.

…… I would keep catching the (dining) car in the act of being recklessly sheathed, lurching waiters and all, in the landscape, while the landscape itself went through a complex system of motion, the daytime moon stubbornly keeping abreast of one’s plate, the distant meadows opening fanwise, the near trees sweeping up on invisible swings toward the track, a parallel rail line all at once committing suicide by anastomosis, a bank of nictitating grass rising, rising, rising, until the little witness of mixed velocities was made to disgorge his portion of omelette aux configures de fraises.

Nabokov’s habit of sprinkling his prose with obscure words is alternately rewarding and problematic. Intervestibular is easily decoded. To understand Westinghousian (Presently, the train stopped with a long-drawn Westinghousian sigh) you need to know that George Westinghouse was the inventor of the railway air brake which seems not too much to ask of a reader. Nictitating** and anastomosis* are words drawn from the medical vocabulary, rarely found in general usage and calculated to leave most readers in need of a dictionary. That said, Nabokov’s vivid tapestry of language brings to life transient but vivid sensations with a flair and economy that few others could achieve.

*anastomosis - medical term for a connection between tubular structures (blood vessels or intestinal tubes).

**nictitating (membrane) - protective membrane that slides back and forth across the eye, not present in humans. Sometimes referred to as “third eyelid”.

1 comment:

Just found your article. I’ve often quoted to folks “six thin black wires” as the most perfect paragraph in English (wish I knew how to pronounce the Russian preamble).

Post a Comment