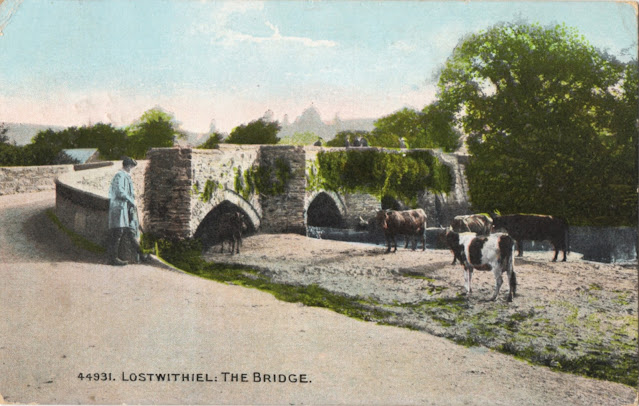

Our annual round up of bridges is again much reduced. One of my favourite Cornish towns is Lostwithiel with its compact grid of narrow streets and a parish church that wouldn’t look out of place in Brittany. Bypassed by history as the River Fowey silted up, robbing the town of its lucrative maritime trade and its status as the county town of Cornwall. Fortunately it wasn’t bypassed by the Cornish Railway which linked it with the wider world and chose to build its principle workshop in the town. The workshops have been converted into apartments but the trains still stop. To reach the railway station, travellers must cross a narrow 15th. century Grade 1 listed stone built bridge over the River Fowey - pedestrians must take their chances with passing vehicles, often resorting to the triangular refuges built out over the piers that support the 5 arch structure. There’s a bucolic postcard from the early years of the last century for comparison.

Wednesday, 29 December 2021

Bridges of 2021

Tuesday, 7 December 2021

Mass Transit in Victorian Britain

There are 20 visible passengers, including the coachman, piled high in defiance of gravity on this horse-drawn carriage. Some look sullen, some apprehensive while others appear quite pleased with themselves. Another 17 bystanders, plus a groom, line the foreground and face the camera. More socially diverse than the passengers behind, they look as if they just drifted into the frame. There are no clues as to location anywhere on the card but the buildings, with their extensive rustication, suggest a business district in a substantial city around the turn of the twentieth century. The camera operator has achieved a remarkable degree of focus enabling each of these faces to be seen in surprising detail. I read somewhere that Apple has a team of 6,000 employees working on the development of the iPhone camera yet they might struggle to produce a better image than this.

Friday, 3 December 2021

Postcard of the Day No. 106, Larkin Factories, Buffalo

This is a conventional promotional postcard - an invitation to admire the inordinate scale of the Larkin Factories activity and the vast extent of its premises in a hand drawn aerial perspective view. The Larkin business was in mail order supplies. As the American settler population infiltrated the most remote regions of the territory in search of unclaimed land, more and more consumers came to depend on the US Mail to keep their rural homesteads supplied with goods. Companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck in Chicago expanded phenomenally by catering to this market and mailed compendious catalogues from shore to shining shore. Within a decade of its foundation as a manufacturer of soap in 1875, the Larkin Company had expanded its product range and sales volume and relaunched as a mail order operation selling direct to the public. Savings made by dispensing with a sales force enabled them to offer discounts and undercut conventional retailers.

The family run Larkin Company was not especially nimble in its response to changes in the market and was in serious decline by 1939 when bankruptcy was narrowly avoided. At the same time Wright’s building was subjected to a series of unsympathetic alterations including the installation of new windows that destroyed the unity of the architect’s vision. After fruitlessly throwing money at a variety of diversification projects, the business finally closed in 1942. Wright’s building was sold to a developer whose plans came to naught - when demolition took place in 1950 the vacant site became a car park. Wright was unexpectedly sanguine - perhaps he lost interest as the Larkin family repeatedly compromised the integrity of his building. It all makes for a fascinating saga and the undisputed authority on the subject is Jack Quinan, whose book, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building, Myth and Fact (MIT Press, 1987) is indispensable.

* Quinan drew attention to the extraordinary ensemble of grain elevators to be seen in Buffalo and reminds us that Wright would have seen them every time his train to or from Chicago passed by them. Wright expressed his admiration for their functionality and uncompromising dominance in the landscape. Quinan speculates that something of their presence might have filtered into the formal geometry of the Larkin building - we can’t know for certain but it’s not wildly implausible.