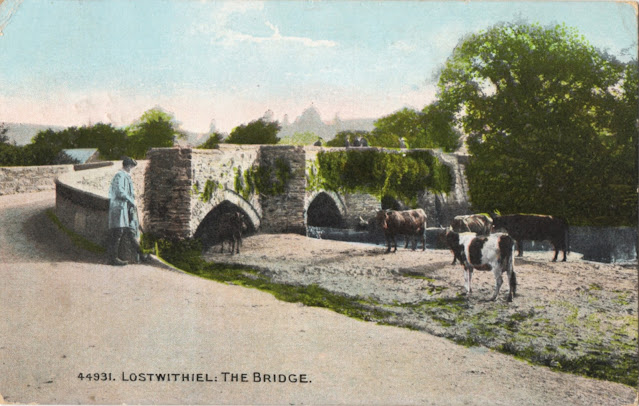

Our annual round up of bridges is again much reduced. One of my favourite Cornish towns is Lostwithiel with its compact grid of narrow streets and a parish church that wouldn’t look out of place in Brittany. Bypassed by history as the River Fowey silted up, robbing the town of its lucrative maritime trade and its status as the county town of Cornwall. Fortunately it wasn’t bypassed by the Cornish Railway which linked it with the wider world and chose to build its principle workshop in the town. The workshops have been converted into apartments but the trains still stop. To reach the railway station, travellers must cross a narrow 15th. century Grade 1 listed stone built bridge over the River Fowey - pedestrians must take their chances with passing vehicles, often resorting to the triangular refuges built out over the piers that support the 5 arch structure. There’s a bucolic postcard from the early years of the last century for comparison.

Wednesday, 29 December 2021

Bridges of 2021

Tuesday, 7 December 2021

Mass Transit in Victorian Britain

There are 20 visible passengers, including the coachman, piled high in defiance of gravity on this horse-drawn carriage. Some look sullen, some apprehensive while others appear quite pleased with themselves. Another 17 bystanders, plus a groom, line the foreground and face the camera. More socially diverse than the passengers behind, they look as if they just drifted into the frame. There are no clues as to location anywhere on the card but the buildings, with their extensive rustication, suggest a business district in a substantial city around the turn of the twentieth century. The camera operator has achieved a remarkable degree of focus enabling each of these faces to be seen in surprising detail. I read somewhere that Apple has a team of 6,000 employees working on the development of the iPhone camera yet they might struggle to produce a better image than this.

Friday, 3 December 2021

Postcard of the Day No. 106, Larkin Factories, Buffalo

This is a conventional promotional postcard - an invitation to admire the inordinate scale of the Larkin Factories activity and the vast extent of its premises in a hand drawn aerial perspective view. The Larkin business was in mail order supplies. As the American settler population infiltrated the most remote regions of the territory in search of unclaimed land, more and more consumers came to depend on the US Mail to keep their rural homesteads supplied with goods. Companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck in Chicago expanded phenomenally by catering to this market and mailed compendious catalogues from shore to shining shore. Within a decade of its foundation as a manufacturer of soap in 1875, the Larkin Company had expanded its product range and sales volume and relaunched as a mail order operation selling direct to the public. Savings made by dispensing with a sales force enabled them to offer discounts and undercut conventional retailers.

The family run Larkin Company was not especially nimble in its response to changes in the market and was in serious decline by 1939 when bankruptcy was narrowly avoided. At the same time Wright’s building was subjected to a series of unsympathetic alterations including the installation of new windows that destroyed the unity of the architect’s vision. After fruitlessly throwing money at a variety of diversification projects, the business finally closed in 1942. Wright’s building was sold to a developer whose plans came to naught - when demolition took place in 1950 the vacant site became a car park. Wright was unexpectedly sanguine - perhaps he lost interest as the Larkin family repeatedly compromised the integrity of his building. It all makes for a fascinating saga and the undisputed authority on the subject is Jack Quinan, whose book, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building, Myth and Fact (MIT Press, 1987) is indispensable.

* Quinan drew attention to the extraordinary ensemble of grain elevators to be seen in Buffalo and reminds us that Wright would have seen them every time his train to or from Chicago passed by them. Wright expressed his admiration for their functionality and uncompromising dominance in the landscape. Quinan speculates that something of their presence might have filtered into the formal geometry of the Larkin building - we can’t know for certain but it’s not wildly implausible.

Tuesday, 30 November 2021

Leipzig 1931

YouTube’s relentless algorithms invade our minds with recommendations designed to trap us in an ever shrinking universe constructed from our innermost prejudices and secret preferences but there are rare moments when they pull a hidden gem from the deep seams of mediocrity and something of unexpected beauty rises to the surface. Which is how this mesmerising, sunlit portrait of a world that was creeping toward a dark decade of destruction and mass murder landed on my screen. For 30 dreamlike minutes we travel through the high summer streets of Leipzig watching the city street life in orbit around a tram driver’s view of a world in motion. None of this was planned - the film was produced for driver training purposes.

Along the way an army of local citizens saunter across the tram tracks - businessmen and lawyers, street cleaners, road repairmen, shop workers, window cleaners carrying ladders, postal workers, and a succession of handcarts and trolleys to and fro, desperate to avoid any unseemly haste, each one calculating their margin of safety to the last second. No sign of the stereotypical Teutonic submission to rules and regulations in 1931 - motorists drive their cars, trucks, and delivery vehicles at every conceivable tangent across the path of the tram. Cyclists, male and female alike, weave through the traffic as if defended by an invisible forcefield. Most alarming are the passing horse-drawn wagons piled high with parcels, packing cases, sacks, beer barrels and items of furniture that make slow and deliberate turns in front of the oncoming tram just seconds away from tragedy.

In the suburbs the tram runs along the centre of broad, straight boulevards lined with trees. Closer to the city we pass along residential streets with tall mansion blocks, streets that contract on the approach to the city before expanding again into grandiloquent squares and plazas linked by busy shopping streets where luxury hotels trade side by side with stately department stores and shopping arcades. Tram tracks divide and converge at complex junctions and snake around opera houses, banks, court rooms, theatres, museums and concert halls. A thousand commercial signs of every dimension announce their services and compete for attention. City landmarks, including the massive Hauptbahnhof and the Hotel Astoria glide past. For the dedicated observer of street life it’s a glorious treat.

Monday, 22 November 2021

Building a Tunnel in New Zealand

There’s a tunnel mouth with a block built portal and some stone retaining walls under construction beneath a steeply rising hillside. A temporary narrow-gauge railway has been built to carry away the spoil and bring materials to the site. Many of the labourers appear to be non-European and a gent in a top hat appears to be supervising activities. The workforce have paused their toil for the camera and a handful of bystanders observe the event from above. The photo bore no caption but I am reliably informed that it shows a tunnel linking the city of Christchurch with the port of Lyttleton on New Zealand’s South Island. Work on the mile long tunnel began in 1861 and trains started running in 1867. It would be 1874 before it was fully complete due to a combination of persistent ingress of water and the challenge of drilling through exceptionally hard rock. There are no passenger trains but it remains in operation for freight trains transporting cargoes from Lyttleton Port. Wikipedia has more.

Saturday, 20 November 2021

Ports of France (1912)

Liebig trade cards taking the collector on a trip around the great sea ports of France - Boulogne, Toulon, Marseille, Brest, Le Havre and Cherbourg. A rather partial selection, almost certain to offend the citizens of St-Nazaire, Bordeaux and Nantes. Each card offers an overview of the port plus two vignettes - one is a local landmark, the second is a character with local connections. A third vignette is an image of the precious meat extract. By way of contrast with these elaborate and floridly coloured compositions a selection of more prosaic images in the form of postcards are included.

Wednesday, 10 November 2021

Postcard of the Day No. 105, Paris - Halles Centrales

Few districts of Vieux Paris have been so frequently romanticised as Les Halles, the city’s produce market that was unceremoniously demolished in 1971 and relocated to the suburbs at Rungis. For more than a century the market was housed in a series of twelve interconnected glass and cast iron pavilions (designed by Victor Baltard) but in the era of the vainglorious Georges Pompidou these masterpieces from the age of cast iron architecture were all too easily swept aside in favour of a meretricious and soulless shopping centre that was so unloved that it had to be replaced in less than three decades. The exuberant vitality that had inspired Emile Zola to write “Le Ventre de Paris” (1873) was lost forever. A significant working class population would be relocated and never again would the neighbouring streets resound with the noise of thousands of heavily laden trucks, trolleys and trailers battling for space - one of the great urban spectacles would be totally erased. These were unnerving times for Parisians who sought to defend their city from the intrusion of grossly inflated modern development. To the south the 56 floors of the Tour Montparnasse were already rising out of the ground and in the west the high-rise blocks at La Défense were taking shape. A vocal campaign to preserve the Baltard pavilions sadly failed thanks to the prevailing infatuation with ostentatious modernism on the part of the ruling Gaullist politicians. Minor concessions were made in the form of enhanced outdoor public space (now the rather dispiriting Jardin Nelson-Mandela) but the scheme progressed largely unamended. The black and white photographs were taken on a trip to Paris in 1974 when it seemed there would be no end to the excavation that had followed the ignoble demolition of Les Halles - it would be another 5 years before this vast hole in the landscape would be filled up with a grandiose interchange between the Métro and the RER and a depressing subterranean retail concrete box.

Wednesday, 27 October 2021

Brussels Midwinter

Scenes from the wintry streets of the Belgian capital just after the war, part of a batch of found photographs taken by a British serviceman on duty in Northern Europe. They make an interesting record of the city in painful transition from war into peace. Powdery snow gathers between the cobblestones and freezes in the gutters while pedestrians hunch up against the cold. The swastikas have been burned and the streets are free of the emblems of occupation. Commercial life is returning and the trams are running. There are posters on display in the Place de Brouckère for Un Bal Surréaliste at the Academie du Beaux Arts (Salle de la Madeleine) on February 8th. - a frivolity that could never have happened under occupation. With privately owned vehicles in short supply, traffic is light and there are long queues at the tram stop. Some landmark buildings can be identified including the Monumental Palais de Justice and the Hotel Metropole (which closed in 2020). The photographer has composed with care and discovered unexpected poetry in the near deserted cobbled streets dusted with snow.