It is strange how those who would die in a ditch to defend a statue of a slave trader have no hesitation in erasing the industrial legacy that is such a vital source of local pride in places like Middlesborough and Redcar that have been ravaged in the era of post-industrialisation. Within 4 hours of taking up her post as Culture Secretary, Ms Nadine Dorries was contacted by Mr Ben Houchen, Tees Valley Mayor, and reversed Historic England’s temporary listing of the Dorman Long coal storage tower at Redcar. Much to the delight of Mr Houchen, it was demolished in the early hours of Sunday September 19 at 1.55 am. Not so much a case of levelling up as levelling down. Ms Dorries is described as a best selling novelist and was commended by Ben Wallace, Minister of Defence as ideal for her new post because her second career shows she is in touch with what ordinary people think. Hilary Mantel is a best selling novelist but I can’t imagine Mr Wallace having much good to say about her. Back to Ms Dorries, she is certainly an accomplished gobshite and avowed opponent of left-wing snowflakes, political correctness, gay marriage and easy access to abortion. So she comes fully armed into the present government’s inspirational ‘war on woke’.

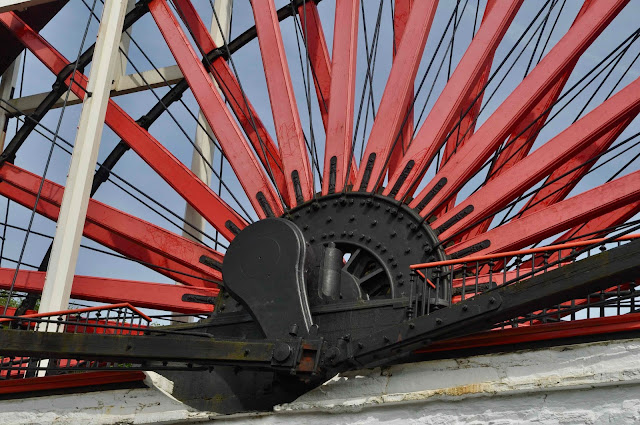

The real villain of this piece is the Mayor of Tees Valley who fought tooth and nail to successfully oppose the local campaign to preserve the redundant blast furnace at Redcar as a significant part of the regional industrial heritage. Demolition of the Redcar steelworks took place in August and the depressing saga of the Mayor’s intrigues and u-turns that made it happen is well told by local blogger, Scott Hunter. Mr Houchen has a Taliban-like enthusiasm for destroying the symbols of the past that sustain a sense of local identity. Replacing them with retail parks, big box fulfilment centres, a freeport for tax evasion and a handful of affordable jerry-built dog-kennels is designed to prepare the locals for a bright shiny future of low-wage, long hours and insecure employment where the profits will be whipped offshore in the blink of an eye. The images of Houchen’s victims come from Google Earth, the industrial panorama (in which the Dorman Long tower can be seen on the skyline in the centre) was photographed by myself from the top of the Transporter Bridge in April 2016.