Another annual selection of pontine postcards - the products of hours of rummaging through bulging shoe boxes stuffed with unsorted postcards, priced at 4 for £1, at Postcard Fairs where the average age is about 75. Most of the cards inspected are depressingly dull but now and then something different will startle the eye - it may be an unorthodox composition, or an inventive viewpoint, or a remarkable quality of printing, or a subject you never expected to see celebrated in this way. The physical discomforts are many - an aching neck, a weary eye and the close proximity of fellow collectors, some of whom lack any concept of boundaries or interest in personal hygiene but the compensation is a growing stack of visual treasures. The show begins with three examples where a viaduct intrudes into an urban setting - Newcastle, Morlaix and Truro. It concludes with some elaborate ironwork from Ohio and Littlehampton. In between are railway viaducts from California and Fontainebleau, a pair of bridges spanning the Niagara River, urban river crossings from Berlin and St. Louis and a primitive wooden bridge over which three young women display their traditional Dutch costume. My favourite example comes from Preston where an enormous viaduct marches over river and countryside alike, foregrounded by neo-classical parkland.

Tuesday, 31 December 2024

Monday, 30 December 2024

Bridges of 2024

This year’s choice of bridges (mostly) crossed and photographed would be very modest but for a visit to Newcastle, which it must be admitted has some fine specimens. From west to east along the Tyne, our first is the High Level Bridge designed by Robert Stephenson (1845-49), with T E Harrison - the rail deck is supported by cast-iron box columns while the road deck is suspended from the rail deck by wrought-iron hangers encased in the box sections. Grade I listed by Historic England. Next is the Swing Bridge of 1868-76, designed and built by W G Armstrong & Co. - a wrought-iron structure supported on cast-iron rollers to allow free movement of shipping, operated by the original Armstrong-built hydraulic engines and controlled from the cupola that spans the deck. Listed by Historic England as a Scheduled Monument and last opened in November 2019. The New Tyne Bridge (1925-28) comes next, built by Dorman & Long of Middlesbrough and designed by Mott, Hay & Anderson - the profile of its single span is often employed as a symbol of the city. The design is a reduced version of the 1916 design produced for the Sydney Harbour Bridge - the four massive pylons, faced in Cornish granite were intended to house warehouses with freight and passenger lifts, none of which came to pass. Grade II* listed by Historic England. Finally to the only bridge over the Tyne designated for pedestrian and cyclist use - the Gateshead Millennium Bridge (1995-2001) designed by Wilkinson Eyre. The deck is suspended from an elegant parabola that can be rotated through 45 degrees to permit the movement of passing ships - a major element in the riverside regeneration project as an artistic and cultural quarter that in turn led to the conjoined coinage of Newcastle-Gateshead.

Finally, two views of the Scarborough Cliff Bridge, a pedestrian footbridge opened in 1827 when it was known as the Spa Bridge, it's an unusual example of a multiple-span cast iron bridge. Connecting the town centre with the Spa, it originally operated as a toll bridge. In the view from the deck the imposing bulk of Cuthbert Brodrick's Grand Hotel looms over the scene. Grade II listed structure.

Tuesday, 3 December 2024

26 rue Vavin, Henri Sauvage, 1912

Adaptability is what distinguishes Henri Sauvage from his architectural contemporaries. After designing an expansive, florid Art Nouveau mansion, Villa Majorelle in Nancy (1901-2) at the age of 28 - he was quick to leave all that biomorphism behind him and by 1912 was busy designing this Parisian apartment building in rue Vavin in Montparnasse with all the clarity of purpose, elegance, simplicity and formal organisation absent from the Art Nouveau stylistic vocabulary. All this well before the Great War snuffed out the last dying embers of the style. In the 1920s and 1930s he steered in the direction of Art Deco - a move that culminated in his redesign of La Samaritaine department store. A man who had mastered the art of staying one step ahead of the competition.

In rue Vavin Sauvage experimented with the idea of stepping back the floors of the building to leave each apartment with outdoor space for leisure or recreation. It was progressive thinking for its time and popular with the occupants, who in the first such case in Paris were members of a cooperative formed to finance the building. Despite being much acclaimed on completion there were few imitators - higher returns could be made with more conventional spatial arrangements. The exterior was clad throughout with gleaming white tiles, making for a contemporary uncluttered appearance. Inspiration came from Otto Wagner and others who had been developing innovative ceramic facades in Vienna for several years. The judicious placement of blue tiles enhances the sculpted forms beneath the balconies and emphasises the window recesses. The last of the photos illustrates the difficulty in sensing the building as a whole thanks to a group of unhelpfully placed trees.

Thursday, 21 November 2024

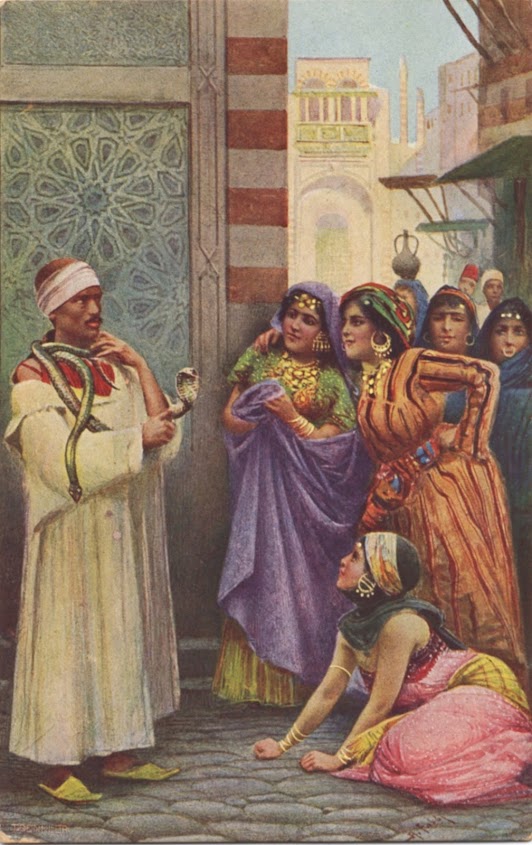

Postcard of the Day No. 114, Snake Handling

An adoring group of female admirers have gathered to pay homage to the courage and skill of the neighbourhood snake handler. Look closer and all may not be as it seems - even though one of the group has fallen to her knees in homage, their expressions suggest they are less impressed and have sensed the defensive air of insecurity on the part of the snake handler. A lack of confidence can be read in his facial tension and his audience appear to be close to dissolving into scornful mirth. The stereotypical imagery falls clearly under the umbrella of Orientalism in its dependence on the exotic. I have another postcard of an Egyptian snake charmer that looks suspiciously like the same person - even the serpents look the same. Other examples are from Myanmar, India and Sri Lanka. Closer to home is the demonic grin of Henry Brusher Mills (1840-1905), celebrity snake catcher of the New Forest, pictured here with a fistful of writhing specimens. Charming was not part of his act. Armed with a forked stick he offered his services to anxious homeowners and it has been calculated he caught over 30,000 snakes in his lifetime - some of which were rendered down to create various dubious potions, others were boiled to reveal their skeletons for sale to tourists. In a rare interlude when not snake bothering, he lit up a pipe and sat for his portrait - the result can be seen here. After his death in 1905 he was buried beneath a rather handsome headstone in the churchyard at Brockenhurst, where you can now take a drink at the Snakecatcher pub.

Thursday, 7 November 2024

Leslie Carr on the cover of “Morris Owner”

Images of motoring subjects made up the greater part of Leslie Carr’s output and he had a close relationship with Morris Motors, one of Britain’s most successful volume car manufacturers of the first half of the 20th. century. Morris Owner magazine was launched in 1924 to appeal to existing and prospective customers and in March 1925 Leslie Carr made his first appearance on the front cover. Many more would follow (as many as 10 in 1926-27) and my selection of 5 is a very small part of his output. Sales were expanding rapidly in the post-war boom as more affordable vehicles attracted the middle class aspiring motorist. The 1920s was the decade of the open air motorist enjoying the freedom of the road in the pre-congestion era. Advertisers were beginning to learn the dark arts of selling dreams and the magazine covers served up a diet of bracing seaside picnics, following the local hunt down empty winding country roads, pitching a tent in deserted beauty spots, bluebell gathering in the woods - all the joys of the new found freedom that car ownership brings. Carr was a remarkably versatile illustrator with the ability to adapt his style to suit any occasion, always with the support of outstanding drawing skills. A speciality was night scenes where the drama and excitement of contrasting pools of deep velvety darkness and incandescent flashes of artificial light are evoked to perfection. Picture editors recognised this and would routinely assign him to produce a cover for the prestigious Motor Show issues as seen here in 1928 and 1929. If I had to choose one it would be November 1929 where the composition is boldly divided by the angular form of the aircraft wing while the tightly drawn subject matter is confined to the lower third.

Sunday, 3 November 2024

Leslie Carr illustrates "By Road, Rail, Air and Sea" (1931)

Fourteen years have passed since I last wrote about the illustrator and poster artist, Leslie Carr and noted the lack of online biographical information. That situation has changed and a lot more detail has emerged about his life and work. We now know he died in the town of his birth, Hove, in 1969 and in his last decade was employed as Art Director for The Motor magazine. In the First World War he served in the Tank Corps and during the Second World War he was a member of the Auxiliary Fire Service. Carr painted a series of paintings of wartime subjects based on his experiences, one of which sold at auction in 2018 for £16,000 after a pre-sale estimate of £200 to £400.

Today’s images come from a Blackie picture book for children published in 1931 titled By Road, Rail, Air and Sea for which Carr supplied the cover art and the majority of illustrations. The cover is a busy dockside scene in which all four transport types are combined in a single image in which areas of unmodified colour are enclosed by crisply incisive contours. In the spirit of the time he mostly employs a sachplakat style, to which he occasionally (and sometimes incongruously) adds some vigorous cross-hatching. Drawings are considered and precise with a subtle and inventive colour palette and at their most radical (the paddle-steamer) display a near-Japanese quality of repose. Examples of his poster work can be seen at Art UK and the Science and Society Picture Library.